Rethinking the Drivers License Test

MIT Mobility Initiative Research Briefing

Jamey Tesler

MIT Mobility Initiative Senior Fellow 2025

Introduction

Approximately 242 million people are licensed to drive in the United States.[1] Almost every single driver had to pass a road test to earn their license.[2] Passing the Driver Test is a ubiquitous, stressful and important experience for many teenagers.[3] This “hallowed rite of passage”[4] has been traditionally viewed as part of becoming an adult in your community.[5] According to the American Automobile Association (AAA), a license “bestows on its owner a sense of maturity, pride and freedom.”[6] This century-old, nationwide public policy fixture, trusted by elected officials, parents and new teen drivers, decides who is safe to drive.[7]

Consequently, there must be a solid foundation of research, data or evidence regarding the positive safety impacts of the Driver Test, correct? The Driver Test is costly and has real policy tradeoffs,[8] so some states must have conducted robust, recent cost-benefit studies that endorsed retaining this conventional practice? As discussed below in detail, there are not rewarding answers to these reasonable assumptions.

We are also experiencing dramatic changes in our vehicles, the rise of mobile devices and the emergence of ADAS[9] capabilities in newer vehicles. At a national level, we live in a time of vastly different policy and political preferences among states. However, despite all these headwinds and disruptions, we have not generated significant innovation or even much variation in the Driver Test across the country.[10] The Driver Test has been remarkably durable.

This split-screen reality (durable test versus rapid technology change) is starker when looked at from a safety perspective. Novice drivers (teenagers) continue to be the most unsafe drivers with too many tragic results on our roads. Notably, policy and safety initiatives including vehicle safety standards, roadway engineering solutions, enhanced enforcement strategies, and targeted interventions to combat the risks of distracted driving have dramatically reduced fatalities and improved safety on our roads over the past few decades. Solutions such as seat belts, airbags and other design features have had measurable positive results. But the last decade has seen progress stall and, potentially, reverse course, despite advancements in vehicle technology. And, yet, somehow the Driver Test has endured and the paradox of how we decide to license new drivers grows.

When a series of COVID-based decisions to suspend or permanently waive the Driver Test in a few states took place, there was a slight crack in the edifice of this long-standing ritual. Likewise, as technology has dramatically begun to alter the role of the driver, vehicles and our streetscape, the need to innovate has meaningfully accelerated. For all these reasons, this Report strives to deeply look at how we determine who gets a new license.

Licensing Matters - Teen Safety Risks

From any vantage point or perspective, in the United States, there is a substantial need to improve roadway safety outcomes, especially for new drivers. The long-term atrophy of the Driver Test, while perhaps understandable, should be an area of focus for safety experts and policymakers. The Driver Test, which almost every new driver still needs to pass, would seem an extraordinarily high value policy lever for most states.

The U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) published early estimates of traffic fatalities for 2024[11], which projected that 39,345 people died in traffic crashes. While a very modest reduction from 2023, we continue to suffer from unacceptable outcomes on our roadways in the United States. While a dispute exists on the precise amount of crashes attributable to human error, there is little argument that we have a substantial need and opportunity to prevent many of the fatalities suffered in the United States on a routine basis.

Considerable research has established that safety risks are most pressing among new drivers, especially teenagers. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the leading cause of death for teenagers are motor vehicle crashes.[12] In a 2024 report, the CDC stated that: “the risk of motor vehicle crashes is higher among teens ages 16–19 than among any other age group. Teen drivers in this age group have a fatal crash rate almost three times as high as drivers ages 20 and older per mile driven.”[13] This same report identified that newly licensed drivers are the highest risk, with a finding “the crash rate per mile driven is about 1.5 times as high for 16-year-old drivers as it is for 18–19-year-old drivers.”[14] In sum, granting a license to a 16 year old is a critical decision. Improving novice driver performance matters greatly in saving lives.

We also have a relatively good understanding of the types of risks, and resulting crashes, that predominate for new drivers. Specifically, and perhaps unexpectedly, crashes are not tied alcohol or high speeds in unusually high levels (McKnight and McKnight, 2003).[15] Actually, “failures of visual scanning (ahead, to the sides and to the rear), attention maintenance, and speed management are responsible, respectively, for 43.6%, 23.0% and 20.8% of the crashes (the causes overlap) among drivers between 16 and 19 years old.” (McKnight & McKnight 2003). In fact, young drivers differ from experienced drivers in these very particular ways, according to a NHTSA 2012 study, suggesting that these vital skills can be learned.[16] New drivers have specific risks that require a targeted education, training and licensing. Consequently, whether these basic skills tested are being taught and tested for teens, before earning their license, matters.

Research Methodology

Research for this report consisted of literature reviews, expert interviews, and web research regarding safety data, articles, industry and academic research papers, policy advocacy websites and attending the MIT Advanced Vehicle Consortium 10-year anniversary conference in May 2025. Interviews were conducted between March 2025 and September 2025 with a range of experts in the government, journalism, advocacy, and academic sectors. These interviews were conducted by phone or on-screen interviews.

An Opportunity Emerges to Rethink Licensing Policy

On April 23, 2020, Governor Brian Kemp issued an executive order suspending the Driver Test as a requirement to get a driver’s license in Georgia.[17] In the spring of 2020, state and local governments confronted unprecedented challenges to continue to deliver basic in-person services due the abrupt public health lockdowns, so understandably they faced hard choices on a range of fronts. Some other states followed suit, including Texas, Wisconsin, and Mississippi;[18] while the majority of others did not, retaining this long-standing element of the licensing process.[19] Some viewed this decision, from a roadway safety perspective, as “catastrophic.”[20] A AAA spokesperson expressed concerns about the safety consequences.[21] While Georgia itself returned in a few months to a modified test, this sudden suspension resulted in some renewed attention about the underlying merits of the Driver Test.[22] Mississippi, however, never returned to the road test and continues to issue licenses without a Driver Test.[23] While this burst of change catalyzed a brief discussion, there was no enduring policy debates and certainly no push back from voters or drivers. No studies exist yet in Mississippi on how this has impacted safety performance.[24] After an eternity of consistent national practice, the Driver Test might be beginning to disappear, with more of a whimper than a roar of opposition.[25]

-

Technology Is Changing the Role of the Driver and Vehicle

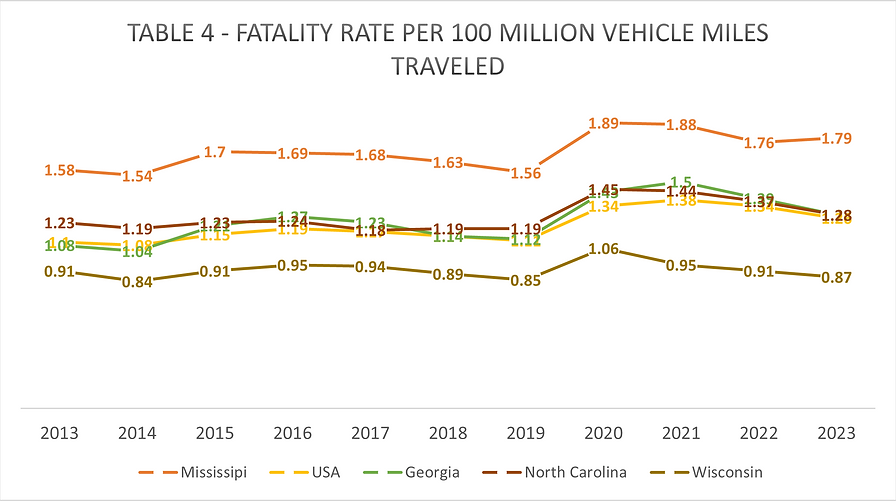

While policy on licensing has been fairly stable until the pandemic, we have experienced a substantial, long-term shift in the concept and role of the human driver and the nature of our vehicles. As a result, the United States has enjoyed an overall, long-term positive trend on fatalities per miles travelled.[26] According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), “[t]the average vehicle on the road in 2012 had an estimated 56% lower fatality risk for its occupants than the average vehicle on the road in the late 1950s.”[27] New cars are likely to have a range of safety-based technology, including electronic stability control, backup cameras (required as of 2018), and blind spot detection systems. Critically, however, this progress has stalled over the past decade.

-

Rising Risks from Distracted Driving

In the past 15 years, new, troubling risks have emerged with the rise and exponential growth of mobile devices. The problems of distracted driving are neither yet fully comprehended nor meaningfully in dispute (3,275 lives lost in 2023).[28] These risks and dangers are particularly acute for new drivers.[29]

-

The Built Environment and Risks are Evolving

In some cities, bike and bus lanes, among other changes, have resulted in a fundamentally altered streetscape. Now, we are beginning to see new forms of transportation, such as e-bikes, scooters, and even robotaxis, enter into the active streetscape. Time will tell the impact of these changes for our mobility network. Clearly, however, if we continue to grant licenses to new drivers, based on a largely unchanged test, then we are introducing rapidly changing and potentially riskier variables.

-

Our Vehicles have Changed

Vehicles themselves have changed over several decades from almost no onboard electronics, to the vastly complex array of electronics, digital displays and sensors in a modern vehicle.[30] If you learned to drive in the 1960s, you are were learning on a manual driving system, meaning all basic skills, like steering, acceleration, braking, and gear changes, were fully manual. Today, greater than 98% of cars sold possess an automatic transmission[31], and a range of automation and driver assistance technologies—including advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS), adaptive cruise control, lane keeping assist, automatic emergency braking and others.[32]

For most of us, the pace of change can be difficult to keep up with. For instance, some vehicles allow various degrees of hands-free driving, including lane changes and other semi-automated highway driving, with examples such as General Motors Super Cruise, Ford BlueCruise and the Tesla Full Self-Driving (FSD) Package.[33] Leaving aside long-term discussions about the benefits and burdens of these changes, what matters, for purposes of this report, is that new human drivers learning in 2025 to drive are confronted with a wholly different landscape than generations ago.

-

Driver’s Role has Changed

While ADAS and other technology changes have vast and debated potential for enhanced safety, these features have already begun to alter the role and responsibilities of a driver.[34] A very recent 2025 study, by the MIT AgeLab and Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) research teams, captured this transformation well.[35] In a October 2021 report, Reagan, Teoh, Cicchino, Gershon, Reimer, Mehler, Seppelt, found that “[t]he longer drivers used the Pilot Assist partial automation system, the more likely they were to become disengaged, with a significant increase in the odds of participants taking both hands off the steering wheel or manipulating a cell phone relative to manual control.”[36]

Said differently, new technology is not a straight line to a safer driving experience, especially for inexperienced drivers. A report by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety in 2024 found that the “[n]ew advanced vehicle technology offers new safety and convenience features to drivers; however, it also stands to change the nature of the driving task as the systems take on more of the driving responsibilities. Driver understanding of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS)—referred to as a mental model—is important in regards to safe and appropriate system usage. If drivers do not understand the technology, especially its limitations, they might use it in situations that it was not designed for, possibly compromising safety.”[37] A separate 2022 Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) report similarly noted the impact associated with ADAS on how we drive.[38] As applied to the Driver Test, in 2019, the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) issued a report on best practices for driver testing associated with ADAS cognizant of the fact that “[m]ost skills tests do not currently accommodate the use of ADAS.”[39] Significantly, today, the motor vehicle agencies have not developed a Driver Test on the basis of these new, but necessary, skills in 2025.

Research has begun to reimagine how we think about the role of human in more advanced vehicles and to suggest how to shift our framework towards a heightened supervisory role.[40] Simon Calvert and Arkady Zgonnikov in a 2025 report said “[a]s vehicles take over more driving tasks, the role of the human driver transitions from an active operator to a passive supervisor. This shift presents several challenges, including the risk of overtrust in the automation (Dikmen and Burns, 2017), deskilling of drivers (Hopkins and Schwanen, 2021), and ambiguity in accountability during critical situations (Santoni de Sio and Mecacci, 2021) … Moreover, there are gaps in drivers’ knowledge of how ADS operate and drivers are not always aware of their responsibilities, leading to potential safety risks (Nordhoff et al., 2023).”[41] Consequently, NHTSA has begun also to rethink the paradigm for human drivers, as partial automation of routine driving functions has progressed over the past decade.[42] Fundamentally, there is a need to reimagine how we test and reskill drivers, migrating to a human supervisor role as ADAS and automation increase (Calvert, Simeon C.; Zgonnikov, Arkady (2025)).[43]

-

The Unchanged Driver Test

With all these changes, a teenager from 1960 might struggle to recognize, let alone drive, today’s vehicles. By contrast, they would definitely remember the Driver Test in most of the United States. In a world of FSD and ADAS features, most states still require a teenager to pass a Test with its familiar practices of backing up in straight line, successfully parallel parking without hitting the curb and a series of other manual-based maneuvers. For those who argue against need for the Driver Test, the “road test is an antiquated holdover from when driving was a much more technical and skilled activity. The machines were more complicated, all cars were manual transmissions, and drivers had to monitor equipment for failures and know how to troubleshoot issues modern cars never experience.”[44]

As this report and other analyses have described, the Driver Test did not just suddenly age out; the research community has long accepted the weakness of the Driver Test. Better practices like Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) rules have been the long-term focus for researchers and safety experts. State law has atrophied and failed to reset as research, technology, vehicles and the built-world have evolved.

The Driver Test in the United States

-

No Uniform Test in the United States

There is no uniform federal license standard or test; and likewise, there is no singular history of the creation and development of the Driver Test. There is no research-backed finding that catalyzed this tradition. Instead, mirroring the organic and exponential growth of the automotive industry, each state established their own training requirements, driver skill testing standards and other ongoing licensing requirements in the first half of the 20th century.

Licensing for drivers first began in Massachusetts and Missouri in 1903.[45] According to AAA, Rhode Island in 1908 began the first test.[46] From there, gradually, and with some differences, states added Knowledge and Driver Test requirements to achieve a driver’s license over the next few decades.[47] The development of this testing regime was a direct consequence of the widespread adoption of automobiles, especially in the 1920s.[48] By the end of the 1920s, approximately 75 percent of households owned a car.[49] With the rapid growth of car ownership, and new car culture, safety issues and reckless driving were growing, leading to many states to add a Driver Test.[50] In this era, state by state, over time, the Driver Test slowly evolved into today’s practice and policy regime; but, importantly, the goal and the skills it tested, were largely based on the perceived challenges and vehicles of that era. Today, 46 states require a Driver Test of some kind, 4 grant waivers based on the completion of driver education (and, now, no test requirement in Mississippi). In his comprehensive article on this topic, Aaron Gordon described the initial origins of the test as a means to screen out bad drivers and, more importantly, how it evolved into today’s skill development test (which envisions, at some point, most candidates passing).[51]

Additionally, in parallel, Driver Education (DE) became standard as a means to teach the basic driving skills necessary to pass the Driver Test. According to a NHTSA study, in 2011, by Chaudhary, Bayer, Ledingham, and Casanova, DE “has been taught in the United States for nearly 100 years, with the first programs emerging between 1910 and 1920 and more formal courses beginning in the 1930s (Stack, 1966; Nichols, 1970; Warner, 1972; Butler, 1982; Public Technology, 1986). Over time it has become a staple of the driving process and is well accepted by the public as a primary method of teaching new drivers the rules of the road and basic driving skills.”[52]

Driver licensing remained through all this time a firmly held feature of state policy, and a formal national standard or driver licensing requirement never existed. This remained true until 2005, when the passage of The REAL ID Act established national standards for state-issued driver's licenses and identification cards to enhance security and prevent fraud. Notably, this law still did not establish safety-based or testing based standards for state issuance of a license.[53] Additionally, a core component of this system is that driver’s licenses are valid, portable and useful across jurisdiction boundaries in the United States.[54]

-

Surprisingly Little Variation Among States

Despite some modest differences in systems, in a 2011 NTSB Report, Haire, Williams, Preusser, Solomon note “[d]river licensing tests in the United States appear to be generally easy with minimal variation among States. … In-vehicle tests are conducted on public roads in most States and on closed courses in a very few States. They are generally short in duration, about 20 minutes, and relatively undemanding in terms of driving maneuvers. The maneuvers typically include parallel parking, and left, right, and three-point turns.”[55] In addition, they found that “there were few apparent differences in test difficulty, on-road test length, time spent preparing for the test, or relative crash risk based on test difficulty.”[56]

-

A Stunningly Durable Public Policy

An important feature of the Driver Test is its remarkable stability over many decades. For such a visible, constant, and large volume experience across every state in the nation, it is surprising that it has retained its basic elements from its origin.[57] In fact, the inertia in this arena is real; once each state establishes its testing requirements and procedures, it becomes hard to change the process. For instance, in New Jersey, a 2008 Teen Driver Study Commission noted that the Driver Test had not been changed in more than 50 years (while also raising doubts about its modern validity).[58] However, as opposed to recommending changes in New Jersey, this Commission deferred the development of a new, effective test to AAMVA. AAMVA, as the national organization for motor vehicle agencies, contracted with NHTSA to develop a non- commercial model testing protocol.[59] This was updated in 2014 and provides the most recent and comprehensive vision of a best practice road test.[60] As the Driver Test is a product of state law and regulation in most jurisdictions, the failure to innovate or recalibrate the test over time might be explainable. One basic reason is that eliminating perceived safety-based test (especially something that generations of people have taken) is not an easy decision for elected officials. With regard to actual test procedures, the 2014 AAMVA report provided a great overview of the ways that states conducted testing.[61]

Research regarding the Driver Test

-

Limited Evidence for the Driver Test as a Predictor of Safety

In 2008, a New Jersey Teen Driver Study Commission asked the key question: “[d]oes the ability to parallel park, perform a K-turn, use turn signals, and brake smoothly, among other things, mean that a novice is ready to drive unsupervised?”[62] Parents and teens would really hope that the answer is a firm yes; but, at best, it appears we really do not know. Or, as expressed well by an overview of the European Test, any Driver Test should be reliable, valid and legitimate.[63]

In a persuasive article on the Driver Test, Aaron Gordon struggled to find support for the Test, explaining that “despite countless hours of research and interviews with automotive historians and safety experts, I’ve come across precious little evidence that driver’s tests are good for anything except propping up the driver education industry. It is time to declare the century-long experiment with driving tests a failure.”[64] In a different report, after the pandemic suspensions, Johnathon Ehsani captured well the dynamics regarding the test by stating “(t)he safety benefit of the driving test comes primarily from the perceived seriousness of the event and the importance that this confers to the right to drive on public roads, rather than from its ability to effectively screen unsafe drivers.”[65]

Likewise, as the Driver Test is inextricably connected to driver education more generally, does this practice have more favorable research support? Actually, extensive research has made a similar conclusion on driver education. In the view of the IIHS, “[f]ormal evaluations of U.S. high school driver education programs indicate little or no reduction in crashes per licensed driver (Lonero & Mayhew, 2010; Mayhew et al., 2014; Mayhew et al., 2017; Peck, 2011).”[66]

This is not apparently a novel conclusion, as the limited value of the Driver Test was identified in studies decades ago. Some studies found “significant, but very small correlations” (Campbell (1958), McRae (1968), and Harrington (1973)), “positive and negative correlations” (Waller and Goo (1968)), and no correlation (Wallace and Crancer (1969) and Dreyer (1976)).[67] While recent events may have brought a renewed interest into this topic, researchers have overwhelming questioned the benefits from driver education[68] and existing testing procedures[69] for some time and advocated a shift toward graduated driver licensing models. Consequently, the yawning gap between the research community and public policy merits a bit more examination.

-

Efforts to Mend, Not End, the Driver Test

Critically, few experts seem to debate the limited predictive nature of the most testing procedures.[70] This does not mean precisely that a Driver Test is without any benefit or value. That is, some efforts have reasonably attempted to heighten results from an improved test or develop a model road test (ADOPT test). These admirable efforts refocus the goal towards baseline skills or competency, diminishing the predictive value a test.

A compelling example was led by AAMVA, in its updated 2014 model test guidelines.[71] This report acknowledges that “[t]he purpose of a road test in driver licensing is to assure that drivers have sufficient skill to be allowed to operate a vehicle without supervision. It is not a test of driving practices or habits. Research has shown that there is no relationship between the extent to which drivers demonstrate such practices as signaling, checking the mirror or staying within the speed limit during a road test, and their use of these practices when they are not being tested. The only test performances that correlate with normal driving are those that require the development of skill, such as maintaining the right path in turns and curves, or stopping at the stop line.”(emphasis added)[72] This report provided an updated version of best practices for states to accomplish this more limited (competency) goal. Similarly, in a 2011 NHTSA-funded report by Haire, Williams, Preusser and Solomon (February 2011), the moderate conclusion was reached that “[d]riving tests are intended to ensure that people using public roadways have a minimum level of competence and are aware of safe driving practices and road law.”[73]

Additionally, an extensive report on the Driver Test was issued by NHTSA in 1981.[74] This report found that “the investigators concluded that the road tests lacked sufficient predictive validity to support their use as a screening device in determining who will be permitted to drive.” This report created a model or recommended road test, which it the called the Automobile Driver On-Road Performance Test “ADOPT.” In its detailed testing protocol, this study did support the benefits of testing “basic vehicle control skills” (page 25), but noted no direct evidence is available as to whether inadequate skills result in crashes. On page 27, the report stated “[m]any of the behaviors identified as appropriate for inclusion in an on-road test of driver performance require the use of sophisticated measurement instruments and techniques which cannot easily be used in an applicant's motor vehicle.”[75] On page 97, the report noted that “[w]hile the Oklahoma test is only one example of a State road test, it is typical of State road tests with respect to the behaviors it attempts to assess and the way it attempts to assess them…it is highly subjective, relying upon examiners to decide what driver performances to assess, where they should be assessed, and how to assess them.”[76] Overall, this report reaches the intriguing conclusion that, at least in 1981, that there was a benefit to using the ADOPT testing method for safety and, likewise, that existing testing regimes lacked validity. In its aftermath, it is hard to identify what, if any, practices were implemented by other states.

-

A Harder Driver Test does not Result in Safer Driving

Another common assumption is that an updated Driver Test, that achieves better safety outcomes for new drivers, simply needs a more intensive version of the current test (longer, harder maneuvers). In fact, Haire, Williams, Preusser and Solomon (2011) concluded that, “[t]he assumption is that more difficult tests require more preparation, thus increasing knowledge and driver competence, and leading to safer driving. This is a logical progression, but the research literature regarding these links is limited and not altogether clear.“ [77] After a comprehensive review of crash rates, testing regimes and levels of difficulty of drivers test (as a proxy for quality of testing regimen), this report could not find a material difference in safety outcomes.[78] In 1978, California studied and reached the same conclusion that adding difficulty or time to a standard driver test, notably, did not result in improvements to subsequent driving records.[79]

-

What Really Matters - Experience

More generally, the shared ground between most researchers and experts is that experience (driving time) is the important determining factor in roadway safety for new drivers. As we lack a controlled or protected environment for gaining this experience, the GDL approach has been most often embraced for achieving better outcomes (more detailed discussion below). But, in the NHTSA 2011 study, Haire, Williams, Preusser and Solomon explained the indirect value of our legacy practices. In particular, “driver license testing can enhance safety, whether or not the tests make a difference on their own. This may be accomplished through delaying licensure, an important mechanism for reducing crash rates. Tests which are more difficult may motivate applicants to spend extra preparation time. This extra preparation can both increase competence and foster delay. Difficult tests (both knowledge and in-vehicle tests) are more likely to have higher failure rates, identifying people not yet ready to drive on public roads, and thus also enhancing delay. Granting licenses to better prepared, slightly older drivers is particularly important in view of the well-established finding that the first few months of licensed driving are extremely risky for young novices.”[80] In essence, the Driver Test, by serving as a delaying function for some novice drivers, can allow more time that correlates to safety benefits. In the 2008 New Jersey study report on teen safety issues, the Commission stated that “[r]esearch shows that it takes more than 1,000 hours of driving before a teen’s crash risk drops significantly.”[81] This comment serves, in conjunction with the analysis cited above, to focus solutions on increasing controlled, monitored driving time and increasing teen driving experience. In other words, there may be some value to retaining a modernized and modified test, as delaying function and as a tool to expand novice driving hours before a full license is obtained.

-

Technology and Vehicles Changes have not yet been fully considered

Most research on the Driver Test has not addressed the progression over recent years of technology. As discussed above, the Driver Test (and any potential indirect benefits) in the United States are not attuned to the present vehicles and changes in the last few years alone. Even the most comprehensive national analysis or state-based research is somewhat aged, certainly pre-dating the changes post-pandemic in teen driving risks. In short, we need not decide in absolute terms whether the Driver Test served for many decades a critical function. Instead, we should reach the easier conclusion that the Driver Test is increasingly becoming obsolete. That is, instead of simply tweaking around the edges or adjusting some elements, we should begin to imagine a new way forward to grant a new driver a license. Technology is not only radically reshaping what it means to drive, but drastically opening up an array of solutions to revitalize testing methods.

-

What has happened in Mississippi?

Since 2021, when Mississippi eliminated its test, what has happened from a safety perspective? To date, no research, data or evidence is readily available to assess this. However, the absence of substantial policy, political or advocacy response is important and consistent with the reality that the Driver Test is not a critical safety checkpoint.[82]

Costs and Downsides of the Driver Test

While the benefits of the Driver Test may be difficult to measure and research on this topic is mixed, the costs and risks associated with conducting a Driver Test are more measurable and identifiable.

First, for every state, there are substantial direct costs with administering this program. These costs will vary widely, especially based on whether the state conducts the testing procedure themselves or contracts to outsource this function. For instance, as part of legislatively-mandated study, the Virginia DMV found that, in Fiscal Year (FY) 2018, approximately 187,000 road skills tests were administered in the Commonwealth. Of those road skills tests administered, over 97,000 were administered by DMV.[83] By contrast, a state like Massachusetts who employs the test examiners directly at the motor vehicle agency will have substantially higher costs. In every instance, these expenses could be applied to other policy goals or initiatives, including other roadway safety initiatives. Separate, any testing procedure, especially one with such high volume and stakes, has certain inherent risks and vulnerabilities. These range from fraud to basic fairness and subjectivity in the test administration and scoring.[84] The Driver Test, with the ability of higher-net worth families to pay for the best driver’s education programs, extra preparation time, access different test sites and pay for additional tests (after a failed test), raises some considerable equity issues.

New Human Drivers-No End in Sight

The path of least resistance might be to embrace the view that new human drivers and, thus, the Driver Test are a thing of the past. Some commentators have made this point quite strongly. A great example is Mario Herger in the book “The Last Driver’s License Holder Has Already Been Born,”[85] with eponymous title that firmly embraces that we are in the final stages of licensing human drivers. Moshe Vardi, Director of Rice University's Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology, has expressed a view that we have 25-35 years remaining in an online forum.[86] If new drivers are quickly disappearing, then the long-term decay of the Driver Test is acceptable as it will simply age out soon.

However, there is little data to support this view; in all likelihood, human driving is not going anywhere soon.[87] In fact, the number of licensed drivers in the United States has steadily increased in this century and in the post-pandemic years.[88] Although it varies considerably on a yearly basis,[89] some estimates for newly licensed drivers over the past few years range from 1.8m new drivers to 2.8m a year.[90] For policymakers and safety advocates, techno-optimism could lead to an unwillingness to adjust or alter standards for human drivers, as these are challenging topics to address. Dr. Bryan Reimer, a research scientist at MIT’s Center for Transportation and Logistics, has stated that as automation increases on our vehicles, we might face a hybrid future with more “novice drivers” who are “more risky than established, trained drivers.”[91] In my view, with no end in sight for human driving of passenger vehicles, the limits of the current practices must be tackled.

The Graduated Driver Licensing Model

GDLs over the past few decades have had a measurable, positive impact on new drivers. One way to contemplate the current policy infrastructure is that we introduced with effective results GDL requirements, while functionally leaving the legacy test undisturbed.

-

GDL Basics

GDL requirements have a few significant differences with the Driver Test, but are both inextricably linked to how a jurisdiction licenses a new driver. Most states have built GDL rules on top of the existing Driver Test model. GDL requirements diminish the binary, pass/fail system as the only step in the licensing process. Instead, by design, as age and experience increase, GDL laws and systems authorize heightened permissions for drivers. As shown above, an undeniable benefit associated with most GDL rules is that they slow down the novice driver from achieving a full, unrestricted license until they gather more experience. Simply put, GDL laws are better targeted at safety outcomes as a policy initiative, distinct from the tradition of the Driver Test.

There are a broad range of potential GDL requirements, and they vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but can include: a mandatory holding period for a learner’s permit; minimum number of hours of supervised driving during the learner’s permit phase; minimum age to obtain an intermediate license; nighttime driving restrictions during intermediate stage; passenger restrictions during the intermediate stage; and minimum age for full licensing.[92] GDL, typically, has three stages: supervision learning, intermediate stage with meaningful restrictions; and unrestricted, full driving.[93]

-

Strong Research Basis

In a departure from the discussion on the Driver Test, substantial and current consensus exists in research and policy circles regarding the safety benefits of GDL requirements.[94] For example, a 2011 study (McCartt and Teoh) cited a dramatic reduction in crash rates for 16-year-olds (68%) and 17-year-olds (53%) (overall 20-40%) based on adoption of GDL laws.[95] Other research has found similar results.[96] A comprehensive 2006 NHTSA study reached a similarly impressive conclusion that restrictions in this form have meaningfully positive safety impacts.[97] A 2007 AAA nationwide comprehensive report also found similar results.[98] “A meta-analysis of 14 studies showed that GDL laws reduced 19% of non-fatal and 21% of fatal crashes among new drivers.[99] Another report suggests that stricter GDL laws (e.g., minimum age for learner’s permit is 16, requirement to have the permit for at least six months, no driving past 10PM with a provisional license) are more impactful, reducing 40% of non-fatal and 38% of fatal crashes.”[100] Separate, the IIHS calculator uses research to show how changes to state provisions might affect collision claims and fatal crash rates among young drivers.[101]

-

Incomplete Adoption and Stalled Progress

In the 1990s and 2000s, widespread adoption of GDL laws was the trend across the United States. However, by 2015, the IIHS, in a study, showed that “progress on enhancing the most effective provisions of GDL has slowed.”[102] While all states have some degree of GDL program, the IIHS stated “if every state adopted the strictest limitations related to five components, the nation would reduce the number of crashes each year by more than 9,500 and save more than 500 lives.”[103] “Many of these countermeasures have been shown to be effective ways of reducing teen crashes” (e.g., Chaudhary, Williams & Nissen, 2007; Ferguson, Williams, Leaf, & Preusser, 1996; Preusser & Tison).[104] One potential explanation is the burgeoning need for lawmakers to focus on distracted driving.[105]

Again, the stalled progress on GDL innovation in the United States, and the corresponding last decade of transformation change in driving, technology and the requisite needs for driver testing create an opportunity. That is, strong evidence supports the continued benefits of upgrading GDL practices. However, with the evolution of vehicles and technology, is our public policy attention best expended on projecting new ways to link GDL principles to today’s problems?

Paths Forward - How to Innovate Beyond the Incumbent Driver Test and Established GDL Frameworks?

As discussed above, while GDL programs are a positive safety measure, we have room to grow these programs already. Furthermore, by eliminating the Driver Test in some states (either temporarily or permanently), and the ensuing silence on this topic, we have the opportunity to break the stagnation on licensing in many states. Technology disruptions add both risks and rewards to the current environment, but can be part of a menu of solutions towards new testing frameworks. What are the potential areas for investment, research or innovation?

-

Modernization of the CDL Testing Requirements

The best model, and opportunity to study for potential licensing reforms, comes from the Commercial Driver License (CDL) Testing process. By way of background, a CDL requires in the view of the federal government, which sets more uniform requirements for CDLs, a “higher level of knowledge, experience, skills, and physical abilities than that required to drive a non-commercial vehicle. In order to obtain a Commercial Driver's License (CDL), an applicant must pass both skills and knowledge testing geared to these higher standards.”[106] In part, this process, and the more intensive requirements, reflect the known risks associated with trucks and heavy-duty vehicles.

In recent years, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) and AAMVA worked together to update the CDL Basic Control Skills Test. This new process has been implemented by many states over the past few years. As noted by the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles in a publicly available presentation, AAMVA’s stated objective was “[t]o create a test method which keeps pace with new technology, industry standards, training practices, jurisdictional needs and driver competencies.”[107] In short, this newly implemented test revised the required tests and the methods of assessment to reflect the changes in technology and expressly achieve better safety outcomes.

Policy changes can be cumbersome, requiring political risk and innovation. However, the modernization of the CDL test, as it is a close analogue to the Driver Test, demonstrates a very feasible, repeatable model. Also, this reform took an incremental approach, it neither abolished the CDL Test nor accepted the past practice as necessity. Said differently, with a strong priority on our updated needs based on modern technology, could AAMVA and/or NHSTA mirror past efforts (like ADOPT) and build a coalition around a modern testing regime?

-

Aviation Framework

In adapting to modern technology, and reimagining the framework for driver testing and training, we should also draw upon the long-established aviation safety system. In aviation, the shift to automation (autopilot and other features) took place decades ago and resulted in a comprehensive reform in the approach to safety. Mendes and Cohen (2022) stated that ”[t]he rise in the use of automation in the aviation sector contributed to a significant decrease in the total number of aviation accidents in the 1980s. The downside was a surge in a new accident type related to human factors such as human-monitoring performance, system awareness, trust, and deskilling.”[108] As discussed above, similar opportunities and risks are emerging with human drivers.[109] Unlike our current training and testing regime, and vehicle technology, “[c]ockpits and flight control systems are designed to optimize human-machine interaction in the safest way possible.”[110] As we add ADAS features, and increasingly depend on autonomous capabilities, the opportunity reconstruct our expectation of the driver to become on-board supervisor will expand.[111]

-

Hazard Perception Training

One area of potential promise, especially to reimagine training and testing protocols, is hazard perception training. As defined in a recent report (Omran, et. al. (2023), ”[o]ne of the most fundamental and essential skills for a driver to possess is the ability to perceive driving hazards.”[112] Further, it stated that [“t]he rate of drivers’ hazard perception has a direct effect on traffic safety. Accordingly, studies have shown that increasing the rate of hazard perception reduces the number of traffic incidents.”[113] NHTSA has a comprehensive webpage dedicated to this topic.[114] One area of potential immediate impact is the Risk Awareness and Perception Training (RAPT) program. NHTSA funded a set of studies to further enhance RAPT[115] and evaluate its effectiveness (Thomas et al., 2016). The evaluation was conducted in California in collaboration with the California DMV. A total of 5,251 drivers 16 to 18 were recruited and assigned to either RAPT or a control group. Outcomes showed a 23.7% lower crash risk for male drivers who received the RAPT training relative to the male drivers in the control group.”[116]

In Great Britain, according to the NTSB 2011 report, “has been a leader in upgrading test requirements and is now considering further changes. In 1999, the test was redesigned, adding about 7 minutes of drive time (Mayhew et al., 2001). Subsequently, a hazard perception test was added, which is taken a few minutes after completing the knowledge test. The applicant is shown 14 one-minute clips of a road traffic journey on a computer screen and is required to click the mouse as soon as a potential hazard is spotted. The faster the hazard is recognized, the more points are awarded.”[117]

There is also promising research that into the concept of risk anticipation skills and incorporating them into DE and testing procedures.[118] “Risk anticipation is the ability to pick up on precursors to potential dangers.”[119] While not taught yet in DE programs, a recent UMASS project developed a new module “Risk Anticipation Training to Enhance Novice Driving (Risk-ATTEND), [that] tries to mitigate some of the most common ways that teens crash, which are intersections, rear-end situations and run-off-the-road scenarios.”[120] Researchers then tested this training in a driving simulator.

-

Simulations

Beyond the use of simulators for risk anticipation, there is a growing area of research and initial evidence into the use of simulators to broadly train novice drivers. For instance, in Australia, “[r]esearchers at the Monash University Accident Research Center have engaged in an extensive development (Regan, Triggs, & Wallace, 1999) and evaluation (Regan, Triggs, & Godley, 2000) of a novice driver-training program. The program that was eventually developed, DriveSmart, combined CD-ROM and simulator training. A total of 14 different content areas in driving were identified as requiring emphasis (e.g., hazard anticipation, attention maintenance).”[121] Researchers in England focused on strategic hazard anticipation that has been identified as critical to reducing novice driver crashes (Chapman, Underwood, & Roberts, 2002).[122]

-

Advanced GDL Models-An Exit Test?

Internationally, there are more advanced GDL models that we should begin to draw upon for a new licensing framework. One area of considerable opportunity is to shift away from the singular concept of a Driver Test. For instance, Haire, Williams, Preusser and Solomon, 2011, noted that “a trend to upgrade tests and to introduce multiple tests: revised tests for advancing from learner permit to initial license, tests that allow progression from one licensing stage to another, and exit tests that must be passed to graduate to full driving privileges.”[123]

Furthermore, in this report, there is a detailed assessment of these models in New Zealand, New South Wales, and a few Canadian provinces. New Zealand, to achieve full license privileges, an “exit test” (known as the Full License Test) is a three-phase on-road test.[124] Ontario, for instance, has two driver tests that you must pass before receiving a full license.[125]

British Columbia and Alberta have also used an advanced “exit” test model to develop more advanced skills, and a related test, prior to granting full licensure.[126] In the United States, Michigan has proceeded with a multi-stage driver education and GDL system.[127]

-

AI-New Models for the Driver Test

While the Driver Test has largely been stagnant in the United States, in Abu Dhabi, for instance, artificial intelligence, machine learning and other technology are being utilized to create a modern driving test.[128] Sensors are being used to “monitor driver behavior, vehicle movements, and compliance with traffic rules.”[129] A similar system has also been used in Morocco with the goal of “enhanced efficiency, accuracy, and fairness in evaluations, reducing wait times and providing standardized assessments.”[130]

Another version of new testing models, using advanced technology, is the “Automated Driving Test Tracks (ADTT)”, a product from IDEMIA.[131] In use in India, “drivers are simply required to drive a vehicle on the test-track and are assessed on their driving speed and other safety characteristics. The result is based on a customized algorithm that analyzes the driver’s conduct during the test.”[132]

-

Vehicle and Driver Monitoring Technology

An extraordinary range of tools, devices, applications and onboard technology, including telematics, enables families to monitor new drivers. There are a vast array of services and features offered, but a few examples tied to the issues of licensing and problem driving enable: 1) the setting of speed limits; 2) regular reports on driving and problem behavior; and 3) audible speed warning sounds.[133] Other applications can identify “rapid acceleration,” monitor “phone usage while driving,” and track “trip history, driver scoring” and “set up geofences.”[134]

In the coming years, with generative AI tools and further sensor development, we possess the ability to develop a full picture of how new drivers are actually driving (and, through technology, provide preventative interventions to assist in better outcome).[135]

-

Insurance Telematics Concepts

GPS devices, sensors and onboard vehicle diagnostics are driving the substantial rise of telematics for fleet owners and operators and their insurance partners. Telematics, in a safety specific setting, are particularly useful to gain an appreciation of driver behavior and risks, before crashes take place.[136] Many fleet owners, and commercial auto insurers, have adopted these tools in recent years.[137]

Research has suggested that feedback provided “to high-risk provisional drivers can enhance driving skills and reduce risky driving behaviors such as speeding and harsh deceleration (Farah et al., 2014, NSW State Insurance Regulatory Authority, 2019, Peer et al., 2020).”[138] Some research provides support for these tools impacting safety outcomes[139], while a more recent study was more mixed on the impact of feedback to new drivers.[140] A 2024 review also found a “divide” in the literature.[141]

Can Technology be linked to an Enhanced GDL Models?

As demonstrated by the research on GDLs, an experience-based, incremental step ladder for new drivers results in improved safety outcomes for this population. Naturally, with the continued onset of in-vehicle technology and telematics, the potential for a further enhancement of GDL programs, incentives and tightened link to our insurance system would seem viable candidates for policy reform. One idea would be to combine these concepts with a more advanced GDL system, such as an exit exam model.

In prior years, the toolbox for policymakers was limited in implementing GDL requirements, but 2025 technology can enhance current and future GDL performance.[142] For instance, past studies speculated that “[m]onitoring equipment may be effective in allowing parents or the licensing authority to monitor teens and provide feedback on how to improve driving skills. The feasibility of using such monitoring equipment on a large scale, however, is not known although several small trials have been conducted and are documented in the literature (compare to McGehee et al., 2007). Given the state-of-the-art, the panel was most comfortable with allocating the monitoring, feedback, and remedial education functions to parents.”[143]

However, the potential of integrating telematics data with a GDL system is worth further analysis. Presently, based on research and experience, GDL concepts, especially in the United States, progress based on time (or age). By incorporating telematics performance data, license systems could be linked or coordinated with the insurance system. In this model, once performance data achieves certain levels of outcomes then directly with an insurer, or indirectly through communication with the licensing authority, full driving privilege could be granted.[144]

Conclusion

One of the most important policy decisions we make is who we grant a driver’s license to. For too long we have let this process atrophy. Not only is there is a paucity evidence, research or results supporting the incumbent practice, but our roads, our cars and our technology have changed. Safety results with teens, and overall, have stalled and too many fatalities continue to transpire. With changing technology, we have a range of promising ways forward to alter substantially how we test and license new drivers. This report has demonstrated that looking back is not the path ahead. Instead, to stimulate action and learning, pilots and research need to be focused on new methods with a dedication towards the skills needed in coming decades to supervise an automobile.

References

[1] https://hedgescompany.com/blog/2024/01/number-of-licensed-drivers-us/

[2] Due to the wide range of skills test, road test, off road test and other forms of behind the wheel testing and terminology commonly used to connote the ways we test potential licensees in the United States, this report refers to all these forms of testing, collectively, as the “Driver Test.” Where the different forms of testing are essential to explain, then I will refer to each form of testing by its more specific name (e.g. road test, skills test, etc.).

[3] There are a few minor exceptions (waivers and post-pandemic states) to this absolute statement. 4 States allow a limited waiver of the Driver Test based on a successful completion of driver education program in their State. (Haire, Williams, Preusser, Solomon (February 2011)) https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf

[4] https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/secret-history-of-the-dmv

[5] At the same time, the Department of Motor Vehicles are often a source of much public frustration. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/secret-history-of-the-dmv (“navigating the ritual space where this test is offered—the Department of Motor Vehicles—is considered an ordeal to be survived”).

[7] Haire, Williams, Preusser, Solomon (February 2011). https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf

[8] See Page 11 for more details.

[9] Advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) “are designed to help drivers with certain driving tasks” and including functions to improve safety or reduce the workload on the driver, including lane departure, self-park, crash avoidance, and blind spot sensors. https://www.aamva.org/topics/advanced-driver-assistance-systems. https://www.aamva.org/topics/advanced-driver-assistance-systems

[10] Haire, Williams, Preusser, Solomon (February 2011). https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf

[11] https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/813710.

[12] https://www.cdc.gov/teen-drivers/risk-factors/index.html

[13] See end-note 12

[14] See end-note 12

[15] Thomas, Blomberg, and Fisher (April 2012). For instance, and notably, while under the influence of alcohol (IIHS, 2008) or while traveling at very high speeds (McKnight & McKnight, 2003) are relatively small causes of fatalities. https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811615.pdf

[16] See Thomas, Blomberg, and Fisher (April 2012). Notably, this research suggests that our licensing process should be focused on these categories of risks (visual scanning, attention maintenance and speed management) to heighten performance for new drivers. https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811615.pdf

[17] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/us/georgia-teen-driving-test-coronavirus.html

[18] https://stateline.org/2020/12/17/suspended-road-tests-give-teens-easier-route-to-licenses/. https://www.weau.com/2023/10/05/covid-era-program-new-wisconsin-drivers-coming-an-end/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7560122/#bib7

[19] As a practical matter, many states paused all driver testing for a period of time, but did not waive the road test. As a consequence, these states, when able to restart their programs, faced a backlog of tests, which meant eligible candidates had to wait several months before getting a road test. Georgia, and others, took an alternative approach and continued granting new licenses during this closed period of time.

[20] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/us/georgia-teen-driving-test-coronavirus.html

[21] See end-note 20

[22] https://www.vice.com/en/article/georgia-driver-license-road-tests-suspended/

https://www.vice.com/en/article/abolish-the-driving-test/

[24] Due to the limited time period for other suspensions, and pandemic issues overall, it may be challenging to determine the impact of these more limited waivers.

[25] At the time of the initial 2020 suspension of the road test in Georgia, I was the Registrar of Motor Vehicles in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As a motor vehicle agency head, I was well aware of these actions, confronted similar policy discussions and, at that time, adamantly opposed to issuing licenses without a road test. This project arises, to a degree, out of an opportunity to revisit those initial views and take a deeper look.

[26] https://www.bts.gov/content/motor-vehicle-safety-data.

[28] https://www.nhtsa.gov/risky-driving/distracted-driving; https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/dangers-texting-while-driving;

[29] https://www.nhtsa.gov/press-releases/put-the-phone-away-or-pay-campaign-2025; also, https://www.cmtelematics.com/distracted-driving-report-2023/

[30] https://www.synopsys.com/glossary/what-is-adas.html

[32] https://www.nhtsa.gov/vehicle-safety/driver-assistance-technologies.

[33] https://bestsellingcarsblog.com/2025/06/media-post-top-5-driver-assisted-cars-in-2025/

[35] https://www.iihs.org/research-areas/bibliography/ref/2312

[36] https://www.iihs.org/news/detail/drivers-let-their-focus-slip-as-they-get-used-to-partial-automation. https://www.iihs.org/research-areas/bibliography/ref/2231

[38] https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/research/safety/22072/22072.pdf.

[40] “[T]he concept of meaningful human control (MHC) has emerged as a key principle in ensuring that these systems operate ethically, safely, and responsible. MHC refers to the idea that even when systems perform complex tasks autonomously, humans should retain the ability to influence or intervene in a way that ensures accountability and aligns the system’s actions with human intentions and values (Santoni de Sio and Van den Hoven, 2018). In the context of ADS, this means that human drivers, regulators, and other stakeholders must maintain meaningful control over vehicles, even if the systems operate autonomously (Calvert et al., 2024).” https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/future-transportation/articles/10.3389/ffutr.2025.1534157/full

[41] Calvert, Simeon C.; Zgonnikov, Arkady (2025) https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/future-transportation/articles/10.3389/ffutr.2025.1534157/full

[42] https://www.nhtsa.gov/vehicle-safety/automated-vehicles-safety

[43] “[H]umans should retain the ability to influence or intervene in a way that ensures accountability and aligns the system’s actions with human intentions and values (Santoni de Sio and Van den Hoven, 2018). In the context of ADS, this means that human drivers, regulators, and other stakeholders must maintain meaningful control over vehicles, even if the systems operate autonomously (Calvert et al., 2024). Calvert, Simeon C.; Zgonnikov, Arkady (2025).

[44] https://www.vice.com/en/article/georgia-driver-license-road-tests-suspended/

[46] See end-note 45

[47] Standard practice among the states is to require a “knowledge test” and a separate Driver Test. While each are important, and the subject of significant policy resources and investment, for purposes of this report, the focus will be on the Driver Test portion of the process.

[48] https://itstillruns.com/history-drivers-license-5552087.html

[49] See end-note 48

[50] https://itstillruns.com/history-drivers-license-5552087.html; https://news.prairiepublic.org/show/dakota-datebook-archive/2022-06-11/traffic-accidents-in-the-1930s

(example of 1930s safety issues); https://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/sr/sr86/86-004.pdf

[51] https://www.vice.com/en/article/georgia-driver-license-road-tests-suspended/

Also, https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/circulars/ec024.pdf

[53] As discussed later, this is notably distinguished from the Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) history and national standards.

[54] Exceptions to interstate transfer of licenses exist with regard to residency, age and for learner’s permits, among other issues.

[55] https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf

[56] See end-note 55

[57] The well-established frustrations with DMVs, and pervasive memes, are in stark contrast to this durable test.

[58] https://www.nj.gov/oag/hts/downloads/TDSC_Report_web.pdf. Another interesting note, in contrast with the oft-stated frustration with the DMVs and the process, in a 1995 NHTSA survey, people overwhelming believed, 86%, that driver education programs were “important.” National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). (1995). "Public Attitudes Toward Traffic Safety, 1995: Highlights Report." (DOT HS 808 076), page 49.

[59] The American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) is a non-profit organization that plays a key role in motor vehicle licensing across the United States, creating consistency and interoperability between the 50 states, District of Columbia, and Canadian provinces who are members.

[61] See end-note 60

[62] https://www.nj.gov/oag/hts/downloads/TDSC_Report_web.pdf

[64] https://www.vice.com/en/article/abolish-the-driving-test/

[65] Ehsani (October 2020). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7560122/#bib7

[66] https://www.iihs.org/research-areas/teenagers; A NHTSA-funded study in 2012 cited numerous reviews “Australia (Wooley, 2000), Britain (Roberts & Kwan, 2002), Canada (Mayhew & Simpson, 2002), Sweden (Engstrom, Gregersen, Hernetkoski, Keskinen, & Nyberg, 10 2003) and the United States (Vernick, Li, Ogaitis, MacKenzie, Baker, & Gielen, 1999; Nichols, 2003), and most recently a comprehensive, international review sponsored by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety (Clinton & Lonero, 2006). These reviews are uniform in failing to identify a crash reduction benefit for standard driver education programs.” Thomas, Blomberg, and Fisher (April 2012). https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811615.pdf. This report also found that “[i]f one of the goals of driver education programs is to provide the skills, knowledge and attitudes necessary for safe driving, then one measure of the success of such programs would be a reduction in the crashes of drivers who had been exposed to driver education programs. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/circulars/ec024.pdf. Unfortunately, like the incumbent Driver Test, “[d]river education has strong “face validity” as a safety measure. Parents think it makes their children safer drivers. (Fuller and Bonney 2003, 2004; Plato and Rasp 1983).”

[67] https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/1318/dot_1318_DS1.pdf. “What is questioned is the effectiveness of the existing road tests. In the light of increasing costs of administration, some have questioned whether all of the various driving tasks assessed during the road tests really reflect the applicant's ability to drive safely. Several studies have attempted to assess the effectiveness of existing road performance tests by correlating test scores with subsequent accident and violation experience. Campbell (1958), McRae (1968), and Harrington (1973) all found significant but very small correlations. Kaestner (1964), as well as Waller and Goo (1968), found both positive and negative correlations, with results dependent on the age and sex of applicants. Wallace and Crancer (1969) and Dreyer (1976) found no correlation.”

[68] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1765489/pdf/v008p00ii3.pdf

[69] https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/1318/dot_1318_DS1.pdf

[70] Thomas, Blomberg, and Fisher (April 2012). https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811615.pdf

[71] See end-note 60

[72] See end-note 60

[73] https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf

[74] https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/1318/dot_1318_DS1.pdf

[75] Importantly, this was over 45 years ago. Consider whether this finding regarding the limits of technology would still be true.

[76] See end-note 74

[77] https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf. “[e]arly evaluations of road tests also did not find any significant safety benefits, nor do individuals who score higher on knowledge tests have more favorable crash or violation records (Mayhew et al., 2001). In the 1990s, California made one of the very few changes in driver assessment that has occurred in recent decades in the United States, adopting a model, competency-based test patterned after a test developed for drivers of commercial vehicles. The test requires about 25 minutes to complete, longer than the standard 10-15, and is considered to be more challenging. Initial research did not find that the new test was associated with any reductions in collision involvement, however; and there is presently no conclusive evidence on the relationship between testing requirements and safety outcomes (Gebers et al., 1998).”

[78] See https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf. page 1. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1765489/pdf/v008p00ii3.pdf (this comprehensive study in 2001 by Mayhew and Simpson demonstrates why education and training procedures have failed to result in improved outcomes for new drivers).

[80] https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf.

[81] https://www.nj.gov/oag/hts/downloads/TDSC_Report_web.pdf

[82] https://www.wlbt.com/2021/09/15/road-test-no-longer-required-obtain-new-drivers-license-mississippi-agency-says/ (early acknowledgement of potential concerns). It is noteworthy how little public discussion this generated. A 2024 bill was considered in Mississippi to restore the test but did not get enacted.

[83] https://www.dmv.virginia.gov/sites/default/files/documents/outsourcing.pdf.

[84] Here are two very recent examples of fraud involving the licensing system. https://www.amny.com/nyc-transit/dmv-road-test-scam-staten-island-07012025/;https://www.enterprisenews.com/story/news/crime/2025/06/11/driving-school-owner-pleads-guilty-to-brockton-rmv-scheme-carlos-cardoso/84154992007/.

[85] Herger, M. (2019). The last driver's license holder has already been born: How rapid advances in automotive technology will disrupt life as we know it and why this is a good thing. McGraw Hill.

[86] https://www.cityam.com/human-drivers-will-be-obsolete-by-2050-as-driverless-technology-takes-over/

[87] https://www.fastcompany.com/90493699/this-is-the-biggest-myth-about-self-driving-cars

[89] Reasons could potentially include changes in license requirements, undocumented licensing bills in CA, NY, MA, and other pandemic driven delays.

[90] https://hedgescompany.com/blog/2024/01/number-of-licensed-drivers-us/

[91] https://www.fastcompany.com/90493699/this-is-the-biggest-myth-about-self-driving-cars

[92] https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/php/publications/graduated-driver-licensing-motor-vehicle-injuries-1.html

[93] See end-note 92

[94] See, for example, this comprehensive, recent summary by the CDC on GDL research and laws. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/php/publications/graduated-driver-licensing-motor-vehicle-injuries-1.html

[95] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/1104317

[96] Master, Fosten, Marshall (2011), JAMA; NIH 2011 Study

[97] https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/gdl_6-20-2006.pdf. Organizations like the IIHS, Governors Highway Safety Association and the National Conference of State Legislatures have a considerable array of research, tools and issues brief that demonstrate in full detail how these programs save lives.

[98] https://aaafoundation.org/nationwide-review-graduated-driver-licensing/

[99] Masten SV, Thomas FD, Korbelak KT, Peck RC, Blomberg RD. Meta-analysis of graduated driver licensing laws. United States. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2015 Nov 1.

[100]Baker SP, Chen LH, Li G. Nationwide review of graduated driver licensing. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. https://ncfrp.org/wp-content/uploads/Teen_Driver_Safety_Guidance.pdf

[101] https://www.iihs.org/research-areas/teenagers/gdl-calculator

[102] https://www.iihs.org/news/detail/strong-graduated-licensing-laws-maximize-benefits. The IIHS noted, that in 2015, only 4 states made upgrades after the IIHS launched its GDL calculator.

[103] Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, December 19, 2013, research report.

[104] July 2011, NHTSA report by Neil K. Chaudhary, Lauren E. Bayer, Katherine A. Ledingham, and Tara D. Casanova https://www.adtsea.org/webfiles/fnitools/documents/nhtsa-driver-ed-practices-selected-states-report.pdf

[105] https://www.iihs.org/news/detail/strong-graduated-licensing-laws-maximize-benefits

[106] https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/CDL

[108] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4211071

[110] https://cacm.acm.org/opinion/autonomous-vehicle-safety/

[111] https://imotions.com/blog/insights/the-human-factors-dirty-dozen-from-aviation-to-automotive/

[112] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10182720/

[113] See end-note 112

[115] The Risk Awareness and Perception Training (RAPT) program is a computer-based training module designed to improve visual scanning, hazard anticipation, and hazard avoidance skills in novice drivers (Pollatsek et al., 2006; Pradhan et al., 2009). https://www.nhtsa.gov/book/countermeasures-that-work/young-drivers/countermeasures/other-strategies-behavior-change

[117] Haire, Williams, Preusser, Solomon (February 2011). https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf

[118] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/21695067231192622?int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.9

[119] https://www.umass.edu/engineering/news/toyota-risk-anticipation

[120] See end-note 119

[121] https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811543.pdf

[122] “The European research project TRAINER took place between 2000 and 2004. The aim of this project, funded by the European Commission and in which various research institutes participated, was the development of new methods for driver training in which computer-based training (CBT) and simulator training were key elements (TRAINER, 2002). The objectives for the simulator training and CBT were derived from the Goals of Driver Education framework, which was the result of a literature review of the causes of the high crash rate of young novice drivers in an earlier European research project called GADGET (Hatakka et al., 2003). In summary, the simulator training and the CBT had some positive effects on the driving performance of learner drivers, and the group that was trained on the MCS did slightly better than the group that was trained on the LCS.[122] There have been several attempts to introduce more targeted hazard anticipation, attention maintenance and vehicle management training in the United States over the past 10 years. Most evaluations have been conducted only on a driving simulator. In a recent study, over 500 novice drivers in California participated in a study of how effective driving simulators were at reducing crash rates among this population of drivers (Allen et al., 2007).” https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811543.pdf

[123] Haire, Williams, Preusser, Solomon (February 2011). https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811440.pdf These regimes were established prior to current tech potential. Next stage, in US, to ease administrative and customer burden is using technology and insurance to ease these transition points and develop a multiple testing regime.

[124] Haire, Williams, Preusser, Solomon (February 2011). “In the first phase, basic driving skills are assessed. In the second phase, applicants are required to identify hazards in urban areas and verbalize these to the examiner after they have been negotiated. In the third phase, applicants are asked to identify prospective hazards in higher speed zones (highways, freeways) and to verbalize these to the examiner and say what actions they are taking to address them. Test completion takes about 55 minutes; about 30 percent of applicants fail the test. New South Wales has a similar multi-stage testing regime.”

[125] https://www.ontario.ca/document/official-mto-drivers-handbook/getting-your-drivers-licence.

[126] Haire, Williams, Preusser, Solomon (February 2011).

[127] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1765489/pdf/v008p00ii3.pdf. “Mayhew et al, 2001, Improvements to driver education/training in a graduated licensing program should be multiphased to harmonize with the graduated licensing process that becomes progressively less restrictive as the novice moves towards full licensure. Despite this prominent feature of graduated licensing, most systems that include driver education/training do so only as part of the learner’s stage. As a consequence, driver education/ training does not fit well with the multiphased graduated licensing system. To rectify this situation, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has recom-mended a two-stage driver education program: a basic driver education course in the learner stage of graduated licensing and a more advanced safety oriented course in the intermediate stage.17 A rudimentary multistaged driver education/ training and graduated licensing system is in place in Michigan.”

[128] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/smart-driving-tests-paradigm-shift-licensing-safer-roads-chokri-1e/

[129] See end-note 128

[130] See end-note 128

[132] See end-note 131

[133] https://www.autoinsurance.com/articles/safe-driving-tech-for-teens/

[134] https://www.thelawofwe.com/technology-for-monitoring-teen-driving-habits/

[135] Some potential innovations include “Advanced AI that can predict potential risky situations based on a driver's habits and provide proactive warnings” and “Virtual reality simulations that use a teen's actual driving data to create personalized training scenarios.” https://www.thelawofwe.com/technology-for-monitoring-teen-driving-habits/

[136] https://www.geotab.com/blog/telematics-insurance/

[137] 54% of large fleets use telematics. https://www.munichre.com/en/insights/business-risks/Leveraging-telematics-to-get-the-most-from-insurance.html

[138] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022437523000609

[139] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022437510000058

[140] See end-note 138

[141] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0001457524000642

[142] A good example of how technology limited GDL implementation in prior years (and now could expand its use case). In 2008, Cambridge Systematics and SJ Engineering conducted a report for New Jersey Department of Transportation and FHWA. “The objective of this project was to assist New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission in determining the feasibility of a removable visual marker for Graduated Driver License (GDL) drivers. The NJ Teen Driver Safety Study Commission issued a report to the Governor and Legislature in March of 2008 in response to concerns over the growing level of fatalities and teen driver injuries in New Jersey. One of the recommendations from the Commission’s report identifies the need to mark vehicles operated by mostly teen Graduated Driver License (GDL) drivers to aid in enforcement of the GDL law.” While this report, in 2008, looked at a range of technology and tactical solutions, in 2025, the universe of solutions (and ease of implementation) would be vastly different. https://www.nj.gov/oag/hts/downloads/TDSC_Report_web.pdf

[143] https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/811543.pdf . “The panel recommended providing parents with a checklist of driving skills and requiring them to assess their teen’s ability to properly perform the skills… The approach could involve both peer and expert feedback to teen drivers in a non-threatening, roundtable type of setting. Recurrent training in the form of more class time, professional driving instruction, or Internet education regarding scanning techniques and alcohol education could be included. Adherence to and enforcement of GDL laws may be the best way to increase safety at this point.”

[144] Data privacy and protection would need to be addressed. In this concept, private driving history could stay between insured and insurer; and communication between insurer and licensing authority could trigger passage of the “exit standard.” While new protocols would need to be established, existing licensing systems and databases routinely communicate and transact directly with insurers.